2021 OsteoSonics- Dental Innovation

September 16, 2021

—a start-up that aims to use focused ultrasound to reduce recovery time in bone-related procedures!

By: Alara Tuncer

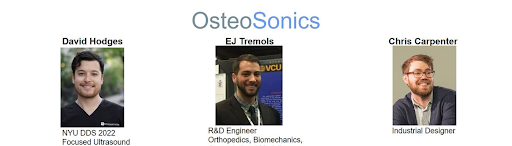

Talking all about “bone, healing, speeding everything up and reducing infections,” I had the opportunity to sit down with David Hodges (NYU College of Dentistry) from OsteoSonics to ask about his brand-new start-up that aims to use focused ultrasound to initiate bone regeneration in dental patients.

Hodges explains how the OsteoSonics technology addresses a major issue with delivering therapeutics or drugs in a dose-dependent manner. Usually, it is difficult to control over how things get released into the body. When designing therapeutic implants, scientists can “layer certain things depending on how it will react with the body [but] it is hard to trigger when to release” the active ingredient. So, OsteoSonics aims to address this by creating a “hydrogel or scaffold that is able to respond to ultrasound and only release drugs when it is triggered.” Hodges goes onto explaining that “theoretically, with this graft you can bring in the patient and zap and release what you want based on the frequency” of the ultrasound. Therefore, this technology will allow to “have control over the graft after it’s already been placed in the body.”

Although OsteoSonics is still in the research phase, this “non-invasive way of using focused ultrasound” is of interest to several fields of medicine and dentistry. Having this overlap has made the research easier. Hodges has been “talking to different clinicians from all sorts of fields [including] orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery and dentistry.” It is “all bone-related, similar concepts biologically, just smaller and lower stakes when talking about dental [procedures]” While this technology has a major “cross-over with orthopedics” as you might imagine, it has also been used “for drug delivery in the brain” due to its specificity. Providing “millimeter or sub-millimeter control,” this technology allows for therapeutics that are “not released in the rest of the body but released in the brain.” Hodges hopes to use this “precise control of dosing [for] tissue grafting in dentistry and oral surgery.”

Yet the main question remains— “what scale is it most useful for?” Hodges states that this could be useful for “anything from dental extractions and implants to joint replacements.” Is it a viable option for “someone who has had cancer in their jaw removed,” in a case where “you want to grow a bone in a huge defect?” Or is it most useful “for routine things, like pulling a tooth and having an implant placed?” Even small routine procedures can take up to “6 months to a year to heal” but this technology can “cut that down to a couple of months.”

Hodges has sought out to turn this research idea into a start-up because “private industry funding seemed like a more effective route” since it was “too slow to go through traditional funding mechanisms” such as NIH grants. He had hoped that getting the “private industry interested” would have a “much faster translation to clinical practice” with “not as many hoops to jump though” to get to a clinician’s office.

As a participant of the Tech Venture Program, Hodges was able to prepare OsteoSonics to the business-side of things, past the pilot studies, for future grants. Fortunately, Hodges started out with this idea right before the tech venture program, so he was able to start “thinking about how it could be commercialized” from the get-go. He notes that there was a “common theme for researchers who were really far along the development process for years” that had to modify their products drastically to cater to the market. But as Hodges was coming as a clinician from the frontlines he was able to observe the problem and what could “cater to clinicians.”

While the Tech Venture program has “the assumption that everything goes perfectly from the technical stand-point [and] your idea works and functions properly” it raises the question of whether it is valuable even after that. As a result, Hodges was introduced to the “whole concept of value propositions.” He explained it to me as thinking about it less as an extraction healing process and “better quality bone” but as convincing “patients to take the treatment because it doesn’t take as long.” Patients that would otherwise turn down the implants due long healing times will now go forward with the treatment knowing that it takes a shorter time to heal. This makes the product a more attractive treatment option, opening doors to more interest and capital.

Although Hodges expects the regulatory side of things to take the longest to get the product into the toolbox of clinicians, he adds that “the exciting part is that the harmful component involving high energy has already been approved for uses within bone.” Since this ultrasound technology has been used for “ablating tumors which have much more adverse effects,” Hodges expects the regulatory approvals to go smoothly.

The future of this product “depends on how interested the researchers” are past the pilot studies. Hodges will find out about the success of the pilot studies over the next year. And therefore, “won’t know how commercially viable” this is until the end of next year. CIE Institute wishes David Hodges and all the researchers working on OsteoSonics the best of luck with their pilot studies and business model. We can’t wait to see how OsteoSonics will revolutionize dental practice and treatment options!